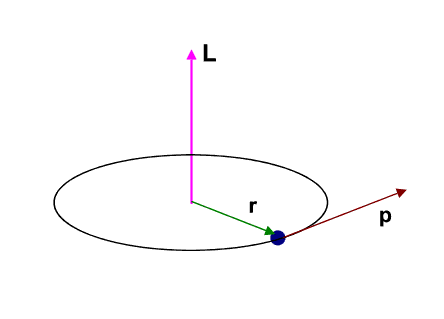

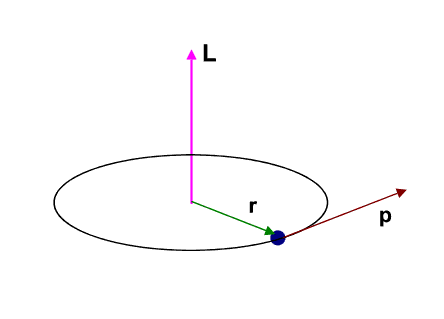

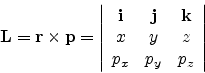

The angular momentum L, as we know from classical mechanics, is given by

x, y, z being the position coordinates and px, py, pz being the corresponding linear momenta.

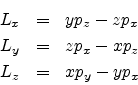

The three angular momentum components are therefore

In quantum mechanics, we work with the corresponding operators, obtained in the position representation by replacing the position coordinates qi by themselves and the momentum coordinates pi by

- i![]()

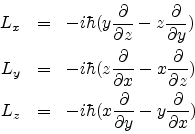

![]() as follows

as follows

We already know what is meant by commutation relations for operators. Let us check out the commutation relations for the angular momentum operators:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ L_{x},L_{y} \right] & = & i\hbar L_{z} \\

\left[ L...

...i\hbar L_{x} \\

\left[ L_{z},L_{x} \right] & = & i\hbar L_{y}

\end{eqnarray*}](elearningimg86.png)

It may also be shown that

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[ L^{2},L_{x} \right] & = & 0 \\

\left[ L^{2},L_{y} \right] & = & 0 \\

\left[ L^{2},L_{z} \right] & = & 0

\end{eqnarray*}](elearningimg87.png) where

where

![]()

We have discussed earlier that any pair of complementary observables whose operators do not commute cannot be determined simultaneously. Hence from the above commutation relations we find that only one component of the angular momentum can be specified precisely. As per convention, we take this component to be Lz, but we could as well have chosen Lx or Ly.

Notice also that L2 commutes with each of the components, hence the magnitude of the angular momentum |![]() | can be specified simultaneously with each of its components.

| can be specified simultaneously with each of its components.

Thus the two fundamental observables are L2 and Lz.

We would soon encounter another angular momentum observable called spin, denoted by S. Hence it would be better if we use a general notation for angular momentum, viz., J. The two fundamental observables, in this notation, are J2 and Jz

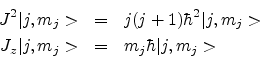

Since J2 and Jz commute, they have the same eigenstate or eigenfunction which is represented in terms of two quantum numbers j and mj as follows:

The corresponding eigenvalues are j(j + 1) and mj. j can have integer or half-integer values and mj = - j... + j in integral steps.

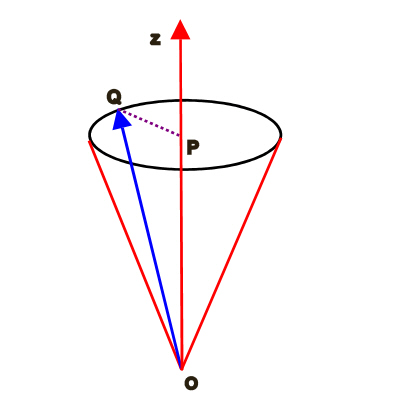

OQ = |![]() | =

| = ![]()

![]() and

OP = Jz = mj

and

OP = Jz = mj![]() . Note that if Jz is specified or fixed we may simultaneously specify only |

. Note that if Jz is specified or fixed we may simultaneously specify only |![]() |. The direction of

|. The direction of ![]() is arbitrary.

In the vector model of angular momentum shown through the figure above,

is arbitrary.

In the vector model of angular momentum shown through the figure above,

![]() may be represented by the sides of a cone ( any one among the many shortest lines joining the vertex of the cone to the periphery of the bottom of the cone, but subject to the quantization condition on Jz), the height of the cone being fixed at Jz. In the process Jx and Jy also become arbitrary.

may be represented by the sides of a cone ( any one among the many shortest lines joining the vertex of the cone to the periphery of the bottom of the cone, but subject to the quantization condition on Jz), the height of the cone being fixed at Jz. In the process Jx and Jy also become arbitrary.